“In the car looking out the windows, the beauty of the artichoke and almond fields, surrounded by twilight’s golden hue, silenced us as well as reminding us of the depth of Dad’s deception about his background. I knew Tom looked out at the scenery with a single thought running through his mind—“a far cry from the slums of Oakland.” The Central Valley was the most dynamic agricultural region in the world and I came from it.

There wasn’t any traffic, as if someone had cleared the roads just for our arrival. The land rolled up to us like waves welcoming us to its shores, its tentacles wrapped around us, me especially, determined not to let me get away for I was a native child, captured and led away from her tribe by a deserter and now was returning home.

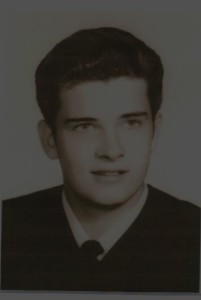

“It’s amazing, isn’t it?” I turned to Tom, who nodded. The scene bore no resemblance to Dad’s description of his boyhood home that he provided whenever one of us asked him “Where do you come from, who were your parents?’ Every year in school we were asked to write about our family history and tell a story about it. Mom always talked about her family and had many stories that I could share in order to complete my assignment but I had two parents and needed something from my father so he had to come up with something.

In retrospect I have to say he was pretty creative in answering my questions about his past but that was a temporary feeling I had when I first learned the truth, probably to disguise my feelings of betrayal. How could he? Instead of city slums I came from rich soil.

I saw a lone worker to my right bent over pulling beets out of soil as black as Texas oil, a silhouette against the sky, his truck parked just to the side. I wondered if that was Dad sixty years ago.

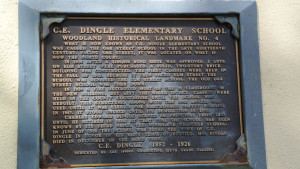

We arrived at our hotel too late to drive thru Woodland. The sun had set, the day’s end sealed off by a diaphanous fog that destroyed the boundary between past and present. I’d entered a new world and wanted my first impression of Woodland to be clear. It’s was a brand new Hampton Inn which surprised us because research on the internet left us with the impression of a small town that only existed to serve the neighboring farms, which didn’t necessarily suggest new hotels and shopping malls, but they were all around us. It’s interstate access, coupled with distance from road-clogging traffic had made our exit a magnet for “Big Box” distribution centers and it was obvious that Woodland was in the mist of a modest boom. A large photograph of Woodland taken in 1925 hung in the lobby. It probably looked that way when Dad was a toddler.

We settled in our room and ate the artichoke dip and chips we bought at the convenience store where we gassed up the car.

“I hated artichokes growing up. Dad insisted all of us eat it because he said that it was good for our blood. That and beets.”

“I never had it growing up.” Tom was born and raised in Indiana and grew up on meat loaf and mashed potatoes.

“Don threw up when Dad forced him to eat it. It was a fight every time Dad served it to him and we all cringed until Don either threw up or ran to his bedroom crying.” I think that was the beginning of the battle between father and son for the artichoke was Dad’s favorite vegetable and Don was determined to reject something forced on him, especially something forced on him by Dad.

He would cook Sunday dinners for us whenever he was home and while we spent most of our life in various towns in the Midwest, surrounded by corn and wheat, he insisted that at least once a month we eat artichokes, an alien and exotic vegetable rarely seen on dinner tables in Iowa. After a lifetime of pressure from him to love it as much as he did, I finally had developed a taste for it. I always asked myself where had he learned to love it and I thought probably from someone in the Navy. But of course he loved it because the artichoke had been a staple at his dinner table growing up and we had just driven thru land abundant with it. It was a staple on everyone’s dinner table that lived in Woodland. I should have taken his love of the artichoke as the first hint that something was wrong with his story of the Oakland slums. But I missed that and other clues.

The next morning the night’s darkness had lifted and we got into the rental car and made a left out of the hotel’s parking lot. Our first stop was Woodland High School because I knew that if they had back issues of their yearbooks, I’d be able to find Ken Mitchell. The town’s Main Street stretched before us as if this might be the Yellow Brick Road to Oz because there was no place like home and Woodland was Dad’s home. On the horizon to the west and north were the Coastal Range and the Capay Valley. It was quiet, not the morning rush hour we experienced daily in Atlanta.

“I knew we moved often because Dad was moving up in the company. But I also thought he was always trying to find a town with a Main Street, just like this. I thought he was looking for a town where he would be comfortable enough to put down roots.”

“Your Dad wasn’t completely comfortable anywhere.” We drove west on E. Main St., past modern day Woodland that consisted of Wal-Mart, Staples, Jack-In-The Box, all built close to the entrance to Interstate 5, which linked Woodland and Sacramento. On the left was even a Chili’s, our favorite family restaurant in Atlanta.

When we crossed over the California Northern Railroad tracks however, there was a notable change. On the right was a tomato cannery and the town before us was a slightly refurbished version of a small town that would not have looked much different fifty years ago. A sign welcomed you to Historic Woodland, City of Trees, and I knew. This was the place that infused Dad with his sense of optimism and American patriotism. It also must have been the stage where his greatest crisis played out, the great rupture that forced his life on an unexpected trajectory from which he never recovered.”